SeQuant

For Symbolics and Numerics in Electronic Structure

by Bimal Gaudel

The Holy Grail: Predictive Accuracy

We want to predict

- structure

- spectra

- reactivity

- …

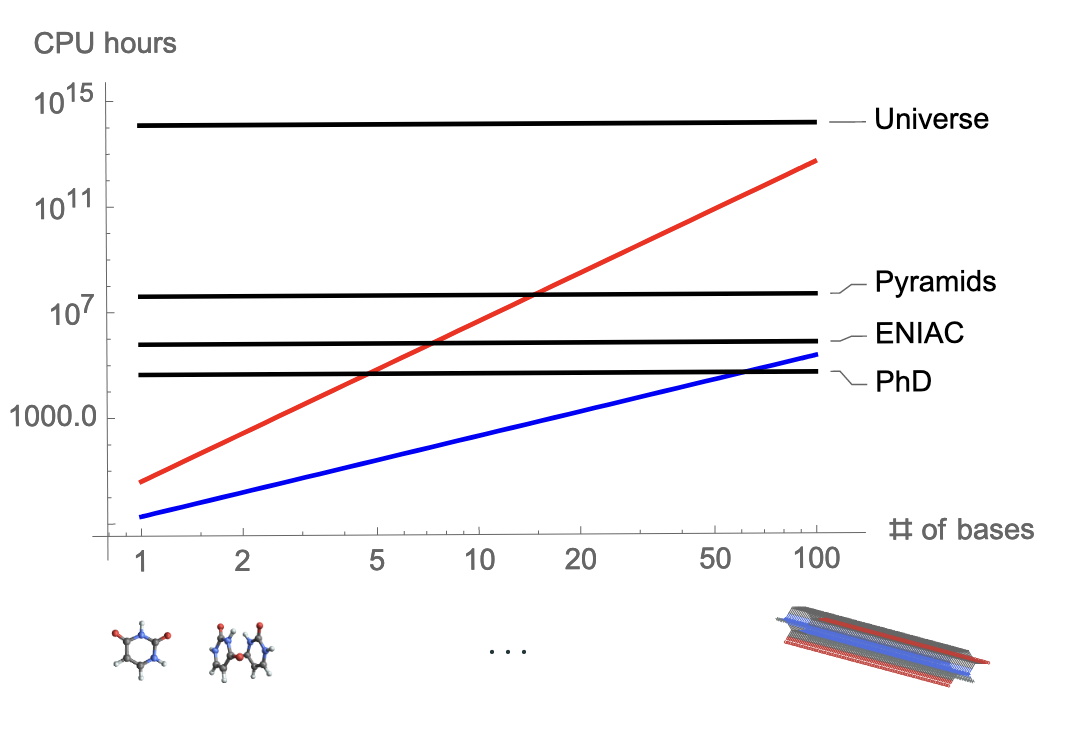

Many-body methods (CC, CI, PT, etc.)

- systematically improvable approximations

- expensive to apply for large systems

Want predictive accuracy on large systems: proteins, complexes, etc.

Theoretical Solutions Exist

We know how to break the scaling wall.

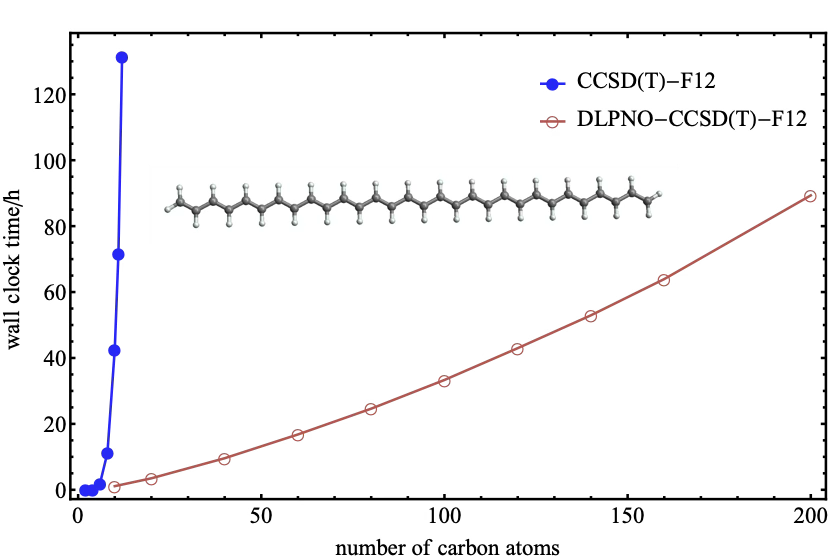

Fragmentation based techniques Gordon et al. (Chem. Rev., 2012)

Formalism that truncate the operator and wavefunctions directly

Use of spatially localized basis sets

- Neese et al. (J. Chem. Phys., 2009)

- Riplinger et al. (J. Chem. Phys., 2016)

- …

- Jiang et al. (J. Chem. Phys., 2025)

CCSD(T) \(\to\) DLPNO-CCSD(T)

\(\mathcal{O}(N^7)\) \(\to\) \(\mathcal{O}(N)\)

Standard vs Reduced-Complexity Coupled Cluster

\[e^{- \opr{T}}\opr{H}e^{\opr{T}}\ket{\Phi} = E\ket{\Phi}\]

\[\opr{T} = \sum_{μ} t_μ \opr{τ}_μ\]

Standard virtuals

\[\opr{τ} \equiv a_{i_1\dots i_k}^\alert{a_1\dots a_k} \equiv a_{a_1}^† \dots a_{a_k}^† a_{i_k}\dots a_{i_1}\]

\[\begin{aligned} R_{a_1 a_2}^{i_1 i_2} = g_{a_1 a_2}^{i_1 i_2} + f_{a_1}^{a_3} t_{a_3 a_2}^{i_1 i_2} + \ldots \end{aligned}\]

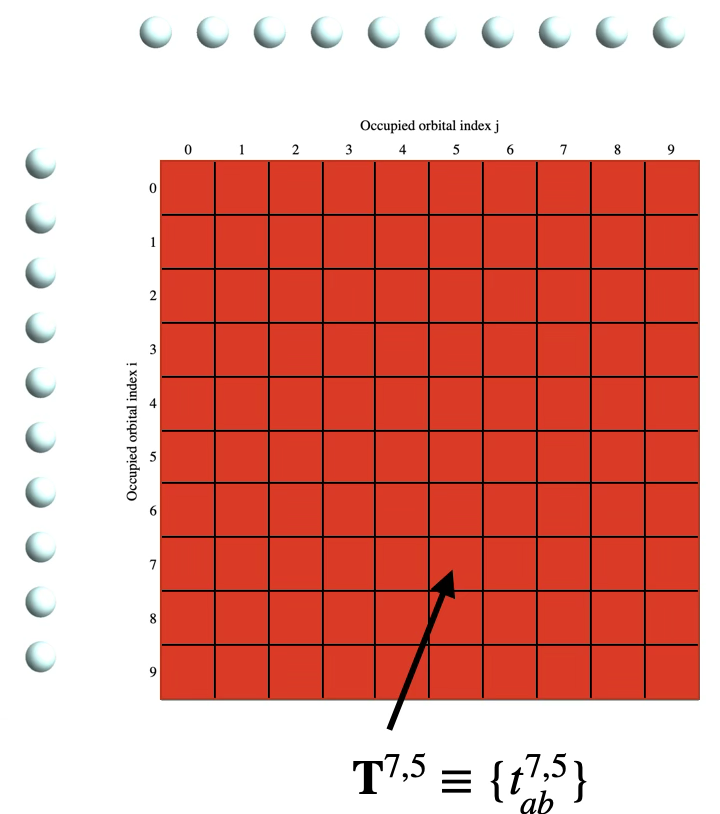

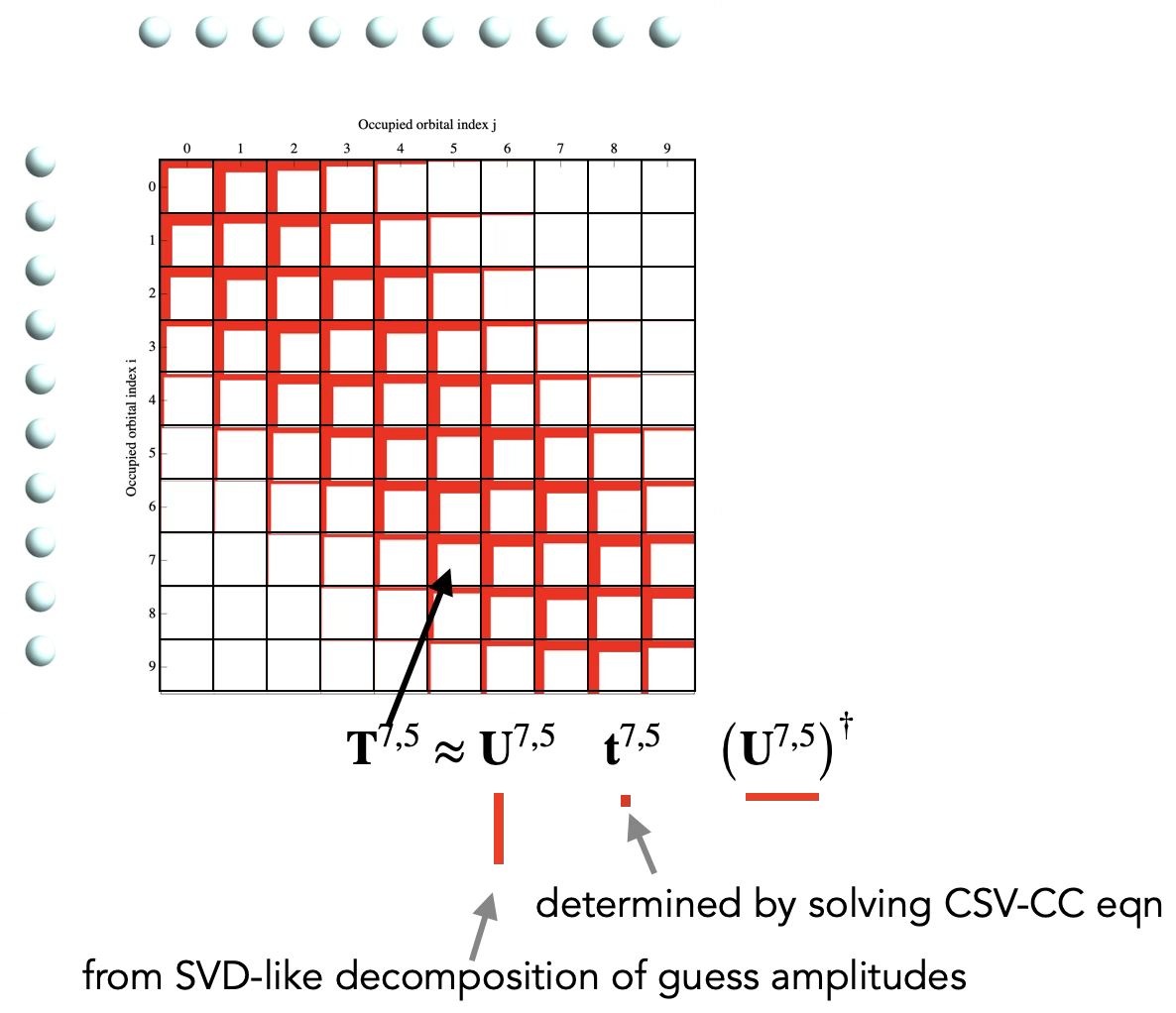

Cluster-specific-virtuals

\[\opr{τ} \equiv a_{i_1 \dots i_k}^\alert{{a_1^{i_1 \dots i_k}}\dots{a_k^{i_1 \dots i_k}}} \equiv a^†_{a_1^{i_1 \dots i_k }} \dots a^†_{a_k^{i_1 \dots i_k}} a_{i_k}\dots a_{i_1}\]

\[\begin{aligned} R_{a_1^{i_1 i_2} a_2^{i_1 i_2}}^{i_1 i_2} = g_{a_1^{i_1 i_2} a_2^{i_1 i_2}}^{i_1 i_2} + f_{a_1^{i_1 i_2}}^{a_3^{i_1 i_2}} t_{a_3^{i_1 i_2} a_2^{i_1 i_2}}^{i_1 i_2} + \ldots \end{aligned}\]

Standard Virtuals CC

Cluster Specific Virtuals (CSV) CC

Conventional vs PNO Formulation

MP2

PNO-MP2

\[\begin{aligned} R_{a_1 a_2}^{i_1 i_2} = &g_{a_1 a_2}^{i_1 i_2} + f_{a_1}^{a_3} t_{a_3 a_2}^{i_1 i_2} \\ &+ f_{a_2}^{a_3} t_{a_1 a_3}^{i_1 i_2} - f_{i_3}^{i_1} t_{a_1 a_2}^{i_3 i_2} - f_{i_3}^{i_2} t_{a_1 a_2}^{i_1 i_3} \end{aligned}\]

\[\begin{aligned} R_{a_1^{i_1 i_2} a_2^{i_1 i_2}}^{i_1 i_2} = &g_{a_1^{i_1 i_2} a_2^{i_1 i_2}}^{i_1 i_2} + f_{a_1^{i_1 i_2}}^{a_3^{i_1 i_2}} t_{a_3^{i_1 i_2} a_2^{i_1 i_2}}^{i_1 i_2} + f_{a_2^{i_1 i_2}}^{a_3^{i_1 i_2}} t_{a_1^{i_1 i_2} a_3^{i_1 i_2}}^{i_1 i_2} \\ &- f_{i_3}^{i_1} t_{a_1^{i_3 i_2} a_2^{i_3 i_2}}^{i_3 i_2} s_{a_1^{i_1 i_2}}^{a_1^{i_3 i_2}} s_{a_2^{i_1 i_2}}^{a_2^{i_3 i_2}} - f_{i_3}^{i_2} t_{a_1^{i_1 i_3} a_2^{i_1 i_3}}^{i_1 i_3} s_{a_1^{i_1 i_2}}^{a_1^{i_1 i_3}} s_{a_2^{i_1 i_2}}^{a_2^{i_1 i_3}} \end{aligned}\]

- familiar algebra of dense/block-sparse tensors with independent dimensions

- covariant algebra \(\to\) affine loop nests, familiar optimization problems

- reduces to dense linear algebra kernels with high FLOP/MOP ratio

- algebra of block-sparse/element-sparse tensors with dependent dimensions

- non-covariant algebra \(\to\) non-affine loop nests

- reduces to dense linear algebra kernels with low FLOP/MOP ratio

Old Problems Renewed in CSV-CC

The Problem of Tensor Network Canonicalization

Consider this tensor network

\[{\overline{g}}_{\alertPink{i_3} i_4}^{\alertPink{a_3} a_4}t_{a_1 \alertPink{a_3}}^{i_1 i_2}t_{a_2 a_4}^{\alertPink{i_3} i_4}\]

- \(t\) tensors are identical (modulo index labeling)

Then we ask: is the following equivalent to the above?

\[{\overline{g}}_{i_4 \alertPink{i_3}}^{a_4 \alertPink{a_3}}t_{a_1 a_4}^{i_1 i_2}t_{a_2 \alertPink{a_3}}^{i_4 \alertPink{i_3}}\]

Turns out yes: just by relabeling the dummy indices \(i_3 \leftrightarrow i_4\) and \(a_3 \leftrightarrow a_4\)

Now consider a pair of tensors with dependent indices

\[\mathbf{T}_1 = \overline{g}_{i_2 a_1^\alertPink{i_1}}^{\alertTeal{a_2}^\alertOrange{i_3} a_3^{i_4}} \text{ and } \mathbf{T}_2 = \overline{g}_{i_2 a_1^{i_4}}^{a_3^\alertPink{i_1} \alertTeal{a_2}^\alertOrange{i_3}}\]

Turns out they are equivalent modulo a phase (\(- 1\)) and index relabeling (\(i_1 \leftrightarrow i_4\)).

\[\mathbf{T}_1 \equiv -1 \times \mathbf{T}_2\left.\right|_{i_1 \leftrightarrow i_4} = - \overline{g}_{i_2 a_1^{i_1}}^{a_3^\alertPink{i_4} \alertTeal{a_2}^\alertOrange{i_3}}\]

Not obvious as in the previous example.

Antisymmetry property of tensor \(\overline{g}\) was used.

Weak algorithms can lead to easy mistakes:

Different but might appear equivalent:

\[g_{i_2 a_1^{i_1}}^{\alertPink{i_3} \alertTeal{a_2^{i_4}}} \qquad g_{i_2 a_1^{i_1}}^{\alertTeal{a_2^{i_4}} \alertPink{i_3}}\]

Equivalent but might appear different:

\[g_{i_2 i_3}^{a_2^{ \alertPink{i_4} \alertTeal{i_5} } a_3^{ \alertPink{i_4} \alertTeal{i_5} }} s_{ \alertPink{i_4} }^{i_2} \qquad g_{i_2 i_3}^{a_2^{ \alertPink{i_4} \alertTeal{i_5} }a_3^{ \alertPink{i_4} \alertTeal{i_5} }} s_{ \alertTeal{i_5} }^{i_2}\]

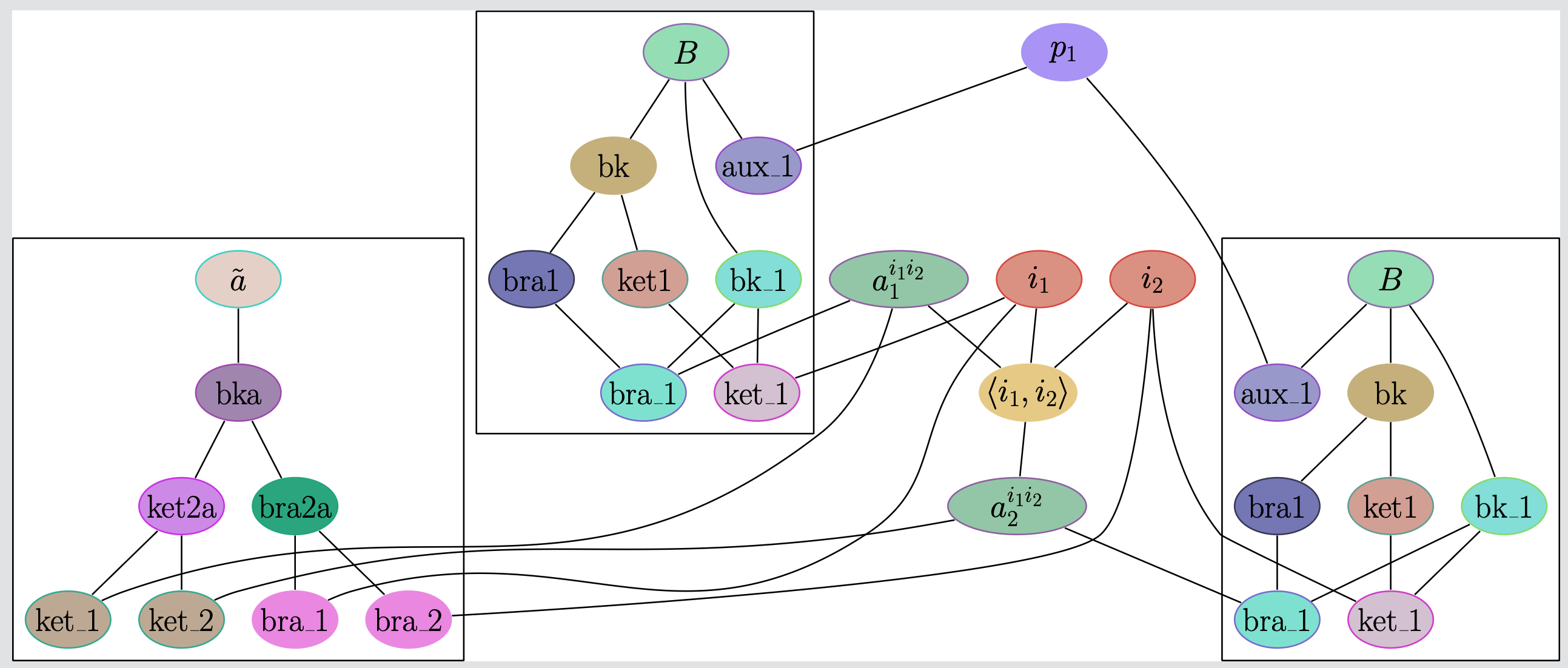

SeQuant’s Solution: Color Graph Canonicalization

- Map the tensors networks to color graphs.

- If the graphs are isomorphic, the tensor networks are identical.

\[B_{a_1^{i_1 i_2}}^{i_1} [p_1] B_{a_2^{i_1 i_2}}^{i_2} [p_1] \tilde{a}_{i_1 i_2}^{a_1^{i_1 i_2} a_2^{i_1 i_2}}\]

- tensor’s label

- braket

- particle columns

- tensor symmetry

- index

- proto-indices (\(a_1^\alert{i_1 i_2}\))

- Standard tensor network canonicalization algorithms, e.g. Butler-Portugal, could be used.

- But they are known to be inefficient (\(\mathcal{O}(N !)\)), particularly when:

- many identical tensors appear in the tensor network

- many tensors with symmetry (e.g. particle symmetry) appear in the network

Color Graph Canonicalization

- Demonstrating equivalence between \[\textbf{TN}_1 (= \tilde{a}_{i_2 i_1}^{a_2 a_1} t_{a_2}^{i_2} t_{a_1}^{i_1})\] and \[\textbf{TN}_2 (= t_{a_2}^{i_1} \tilde{a}_{i_2 i_1}^{a_2 a_1} t_{a_1}^{i_2}).\]

- Visualized vertex ordering and regrouping for corresponding tensors.

- Sign change originates from the net permutation of slots in \(\tilde{a}\) tensor (\(\textbf{TN}_2\)).

- Normalization: renamed dummy indices & lexicographically sorted the tensors

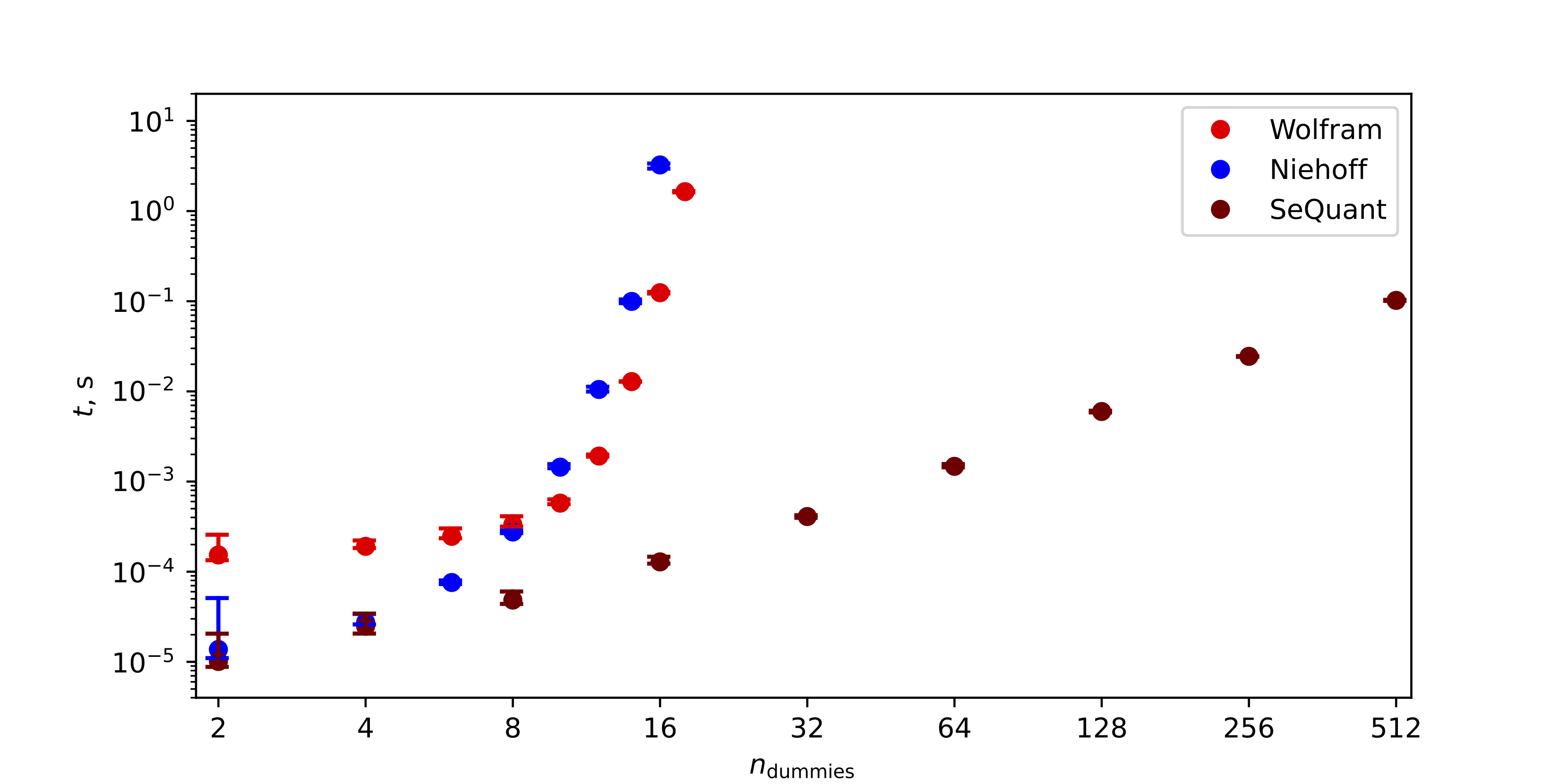

Performance of Colored Graph Canonicalizer

Canonicalizing \(D_{i_1 i_2} D_{i_3 i_4} \dots D_{i_{N-1} i_N} U^{π[i_1 \dots i_N]}\)

Our graph-theoretic solution surpasses Butler-Portugal-based methods in speed

Old Problems Renewed in CSV-CC (again..)

How to implement?

- Non CSV method development itself is pretty challenging.

- Tedious and error-prone

- CSV method devlopment is adds to the complexity

- non-covariant tensor algebra

- block-sparse “ragged” data structure

Non-affine Algebra

\[f_{a_1}^{a_3} t_{a_3 a_2}^{i_1 i_2}\]

\[f_{a_1^{i_1 i_2}}^{a_3^{i_1 i_2}} t_{a_3^{i_1 i_2} a_2^{i_1 i_2}}^{i_1 i_2}\]

\[R(a,b,i,j) \leftarrow \sum_c f(a,c) \times t(c,b,i,j)\]

- tensors can be assumed to be hyper-rectangle (tensor-of-sub-tensors)

- we will call them tensor-of-scalars (ToS)

for i in range(0, I):

for j in range(0, J):

# Bounds are functions of (i,j)

curr_A = get_dim_a(i, j)

curr_C = get_dim_c(i, j)

for a in range(0, curr_A): # <--- Dependent bound

for b in range(0, curr_B): # <--- Dependent bound

for c in range(0, curr_C): # <--- Dependent bound

# Indexing requires pointer chasing

R[...][a][b] += F[a][c] * T[...][c][b]- tensors are ‘ragged’ (tensor-of-tensors)

- we will call them tensor-of-tensors (ToT)

Implementation

- A possibility: sparse tensor storage formats eg. compressed sparse row (CSR).

- This style will silence erroneous implementations (misses the semantics). \[\sum_{c^\alert{i j}} f(a^\alert{i j},c^\alert{i j}) \times t(c^\alert{i j},b^\alert{i j},i,j) \not\equiv \underset{\text{CSR view}}{\sum_c f(a,c) \times t(c,b,i,j)}\]

- We needed a tool that enables rapid proto-typing.

We asked: could we make use of an existing tensor framework?

Understanding a general product between Tensor-of-Scalars (ToS)

\[\sum_{k} A\left(i, j, k, l \right) \times B \left(j,k,l,m\right) \to C\left(m,i,j,l\right)\]

\[i j k l\alert{,}j k l m \to m i j l\]

Semantics

- batched indices: \(j\) and \(l\).

- free indices: \(i\) and \(m\).

- contracted index: \(k\).

Foundation

The properties of the scalar ring.

- scalar \(\alert{\times}\) scalar \(\to\) scalar

- scalar \(\alert{+}\) scalar \(\to\) scalar

- …

Implementation

We asked: could we make use of an existing tensor framework?

\[\sum_{c^\alert{i j}} f(a^\alert{i j},c^\alert{i j}) \times t(c^\alert{i j},b^\alert{i j},i,j)\]

ToT

\[i j\alertTeal{;} a^{i j} c^{i j}\alert{,} i j\alertTeal{;} b^{i j} c^{i j} \to i j\alertTeal{;} a^{i j} b^{i j}\]

If we view the inner tensors of a ToT as ‘generalized scalars’ \[i j\alert{,} i j \to i j\]

We have not defined the ring-like equivalence for these generalized scalars yet.

Implementation

Viewing the CSV-tensors with dependent indices as ToTs gives a powerful starting point to implement CSV-methods.

Built-in semantics

\[i j\alertTeal{;} a^{i j} c^{i j}\alert{,} i j\alertTeal{;} b^{i j} c^{i j} \to i j\alertTeal{;} a^{i j} b^{i j}\]

\(\{i, j\}\) determines which inner tensors can contract. Less error prone.

Familiar dense/block-sparse tensor algebra

\[i j\alert{,} i j \to i j\]

- No need to worry about the raggedness.

- Tensor framework’s features availed from the outer tensor’s perspective

- block-sparsity

- data distribution

- …

Implementation

Ring-like operations support for ToT

Implemented in TiledArray.

Automated Development

One of the major goals was to automate the many-body method implementation.

Common steps of method development

- Symbolic derivation

- Optimization for evaluation

- Code implementation

- Every step is error-prone and tedious for manual implementation

- Difficult to make it ‘performance portable’

- can we easily port to different hardwares?

- will it be usable in a decade with little friction?

… from then (\(> 30\) yr) to now

Long realized automation is crucial

- Janssen & Schaefer (Theor. Chim. Acta, 1991)

- Hirata (J. Phys. Chem. A, 2003)

- Kállay & Surján (J. Chem. Phys., 2001)

- Engels-Putzka & Hanrath (J. Chem. Phys., 2011)

- Evangelista (J. Chem. Phys., 2022)

- Lechner et al. (Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2024)

- Liebenthal et al. (J. Phys. Chem. A, 2025)

This work

- Motivated by the lack of support for CSV-methods.

- Supports standard many-body method development too.

Automated Development

We have designed SeQuant after a modern three-stage compiler.

Three stages: Front end

- general compiler fronted parses the code into an abstract syntax tree (AST)

- AST encodes different operations/symantics between nodes

- In SeQuant: the

Exprobjects from method derivation serve as the AST

\(g_{ij}^{a^{ij}b^{ij}}\left( 2t_{a^{ij}b^{ij}}^{ij} - t_{a^{ij}b^{ij}}^{ji} \right)\)

Automated Development

We have designed SeQuant after a modern three-stage compiler.

Three stages: Middle end

Intermediate Representation (IR)

- Preparatory stage for the backend/evaluation.

- Some semantics of tensor algebra might be lost as part of optimization.

- Notice the physical layout of the two \(t\) tensors.

\(g_{ij}^{a^{ij}b^{ij}}\left( 2t_{a^{ij}b^{ij}}^{ij} - t_{a^{ij}b^{ij}}^{ji} \right)\)

Automated Development

We have designed SeQuant after a modern three-stage compiler.

Three stages: Middle end (Optimizations)

\(\text{O}, \text{V}\): dimension of indices \(i_k\) and \(a_k\)s. With \(\text{V} \gg \text{O}\)

\[(g_{\alert{i_3} i_4}^{a_3 a_4} t_{a_1 a_2}^{i_1 \alert{i_3}}) t_{a_3 a_4}^{i_2 i_4}\]

\[\text{O}^3\text{V}^4\]

\[(g_{i_3 i_4}^\alert{a_3 a_4} t_\alert{a_3 a_4}^{i_2 i_4}) t_{a_1 a_2}^{i_1 i_3}\]

\[\text{O}^3\text{V}^2\]

- Robustly implemented for non-CSV methods using dynamic programming.

- Lai et al. (Chem. Phys. Lett., 2012)

- We have not explored much for CSV methods

- Less severe effects from contraction ordering (at least for FLOPs).

- A research problem of its own.

\[\frac{1}{16}\alert{(\bar{g}_{k l}^{c d} t_{c d}^{i j})} t_{a b}^{k l} + \frac{1}{8}\alert{(\bar{g}_{k l}^{c d} t_{c d}^{i j})} t_{a}^{k} t_{b}^{l}\]

- Identify the repeating sub-expressions (highlighted)

- Evaluate and store \(I_{k l}^{i j} \leftarrow \bar{g}_{k l}^{c d} t_{c d}^{i j}\)

- this is done as part of the evaluation of the ‘first’ term

- Reuse from cache \(I_{k l}^{i j}\)

- this is done as part of the evaluation of the ‘second’ term

Automated Development

Three stages: Middle end (Canonicalizer for semantic enforcing)

The graph canonicalizer again is crucial at this stage.

- Provides the canonical identity for CSE

- Provides the canonical index labels

- for unambiguous storage and retrieval from cache

\[\mathbf{T}_1 = \overline{g}_{i_2 a_1^\alertPink{i_1}}^{\alertTeal{a_2}^\alertOrange{i_3} a_3^{i_4}} \text{ and } \mathbf{T}_2 = \overline{g}_{i_2 a_1^{i_4}}^{a_3^\alertPink{i_1} \alertTeal{a_2}^\alertOrange{i_3}}\] \[\mathbf{T}_1 \equiv \mathbf{T}_2\] \[\left(i_4,i_3,i_1,i_2;a_1^{i_1},a_3^{i_4},a_2^{i_3}\right) \text{ and } \left(i_1,i_3,i_4,i_2;a_1^{i_1},a_3^{i_4},a_2^{i_3}\right) \text{ with a phase of } (-1)\]

Automated Development

Three stages: Back end (Interpreter)

The interpreter builds on top of the IR.

Handles

- diverse data types resulting from the IR nodes

- scalars, ToS, ToT

- working with such heterogeneous result types is abstracted over a

Resultabstract class - leveraging this abstraction, the interpreter allows plug-and-play of different numerical backends

- TiledArray

- BTAS

Automated Development

Three stages: Back end (Interpreter)

The interpreter builds on top of the IR.

Results

SeQuant—a C++ library/framework for

Symbolic Derivation: wide range of theories: including PNO-CC

Automatic Evaluation: let code compilation not break our workflow

Performant and Scalable:

- implements various optimizations for improved performance

- supports auto evaluation on HPC nodes out of the box (using

TiledArraytensor framework)

Extensible Architecture: more numerical tensor frameworks and quantum chemistry packages? welcome

- e.g. Köhn group, University of Stuttgart

Results

Automation of standard many-body methods

SeQuant has accelerated the development by avoiding algebraic complexity of derivation, optimization, and evaluation in the following works.

- Transcorrelated F12 Methods (exploration of new ansatze) Masteran et al. (J. Chem. Theory Comput., 2025)

- Discovering 3CC could be surprisingly better than CCSD(T) Teke et al. (J. Phys. Chem. A, 2024)

- Discovering human error Masteran et al. (J. Chem. Phys., 2023)

- …

Results

How about CSV-CC

- We can automatically implement CSV-CC methods of arbitrary order

- We can already reproduce the results of manually implemented PNO-CC

- Clement et al. (J. Chem. Theory Comput., 2018)

However

We are facing some challenges regarding memory bottlenecks.

Broader Impact

How does this change the field?

- Empowering Innovation: Theorists can now ask “What if?” without fearing years of coding.

- Prototyping happens in days, not PhDs.

- Lowering the Barrier: Scientists can focus on theory, not software architecture.

- Reproducibility:

- Automation eliminates human error.

- The separation of symbolic logic from numerical execution guarantees verifiability.

Future Research Questions:

- Properties & Response Theory: Can we automate the derivation of polarizabilities and magnetic properties?.

- New Theoretical Classes: Extending the graph-based engine to Relativistic QM and Advanced Multireference theories.

- Emerging Hardware: Targeting GPUs and accelerators by simply swapping the backend numerical library.

Moving closer to the ultimate goal:

A fully automated workflow where we design, test, and deploy the next generation of predictive theories with unprecedented speed.

Acknowledgments

- Prof. Edward Valeev

- Department of Chemistry

- Joli, Esker, John

- Collaborators

- Robert, Saurabh, Saday

- My research committee

- T. Daniel Crawford

- Diego Troya

- Nicholas Mayhall

- Current and past group members

- People from all walks of my life

SeQuant for Symbolics and Numerics